How to Use Electronic Charts

Watch Out

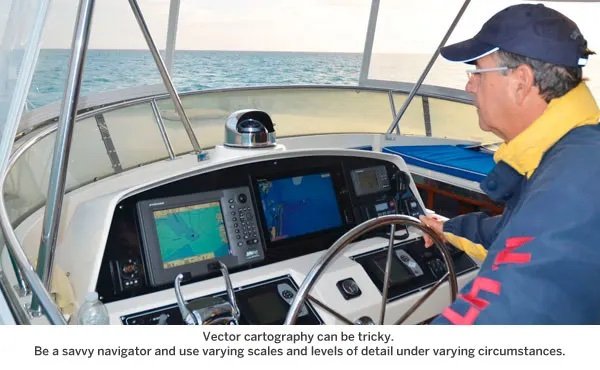

E-Cartography is fabulous stuff, but it can be deceptive. Here’s how to avoid the pitfalls.

In November 2014, the 65-foot sailing yacht Vestas Wind slammed into the remote Cargados Carajos Shoals in the Indian Ocean at 19 knots during the round-the-world Volvo Ocean Race. The vessel lifted and pounded, scraped and slewed about on the reef, snapping rudders and ripping the transom adrift. The crew survived but they had no idea what they had hit because they had no idea that there was anything to hit.

News of the incident traveled far beyond the exalted realm of ocean racing, and rightly so. How could the world’s most elite ocean navigators, equipped with top-of-the-line instruments, dash their high-tech racehorse onto a charted reef? Unsurprisingly, the skipper acknowledged later, human error was at the heart of it.

Of course, there’s no question that even the most accomplished mariner can misinterpret information, fail to maximize resources, and leave the wrong stone unturned. If it can happen to such experts, it can happen to any of us. But the incident raises crucial, and often poorly understood, issues concerning the nature of electronic charts, their limitations, and how they can manipulate our perception of risk in ways that expose us to new kinds of human error.

Let’s start by acknowledging that electronic charts are here to stay because they do, in fact, offer many advantages. Their chief benefit is that your position and direction of travel are displayed in real time, right there, on the chart with all the accuracy of a satellite-navigation system. The real-time display eliminates the delay involved with manual plotting, and the very real potential for human error when transferring bearings, ranges, and even GPS coordinates onto a paper chart. The ability to update charts electronically is an obvious boon too, not to mention that electronic charts sidestep the storage considerations that go with paper charts.

What!? Not Foolproof!?

Next, we need to revisit the difference between raster charts and vector charts. Raster charts are electronic facsimiles of paper charts. You can zoom in to make details bigger, or zoom out for a wider perspective. But the charted information—navaids, isolated dangers, and spot soundings—does not come and go with the zooming. It just gets bigger or smaller, like looking at a map with, or without, a magnifying glass. In this sense, raster charts are relatively foolproof. The user cannot change what is shown on the chart: what you see is what you get.

[image]

A vector display showing so much extra detail that it becomes confusing and perhaps dangerous.

[image]

This version retains the scale but usefully cuts detail.

One mouse click produces a slightly smaller scale with radical—and again perhaps dangerous—consequences for what the navigator sees.

Vector charts, on the other hand, present a staggering mineshaft of functionality with vast capabilities, along with wide latitude for misinterpretation. Stored information about a charted object can be summoned with the click of a mouse. A depth contour can be inserted based on your specific vessel characteristics. Electronic “post its” can be embedded as reminders to get the anchor ready, slow down, or make a radio call, and any number of alarms can be customized to your needs. Whereas a raster chart is no more than a paper chart in an electronic format, a vector chart is, in one sense, a blank canvas, with many of the implied choices. There is a lot to understand and misunderstand about what you are seeing, or not seeing, on a vector chart.

For instance, information on a vector chart can be made to literally appear or disappear by zooming in or out, or by selecting different displays (See the accompanying screenshots for a better understanding of this concept). It is also possible to show so much information on a vector chart that the screen becomes cluttered, thereby obscuring essential information. Both the skipper and the navigator of Vestas Wind have made comments suggesting that it was a failure to zoom in far enough when planning (and monitoring) their route that resulted in them not seeing the shoals that lay in their path. Charles Caudrelier, skipper of Team Dongfeng, another Volvo Ocean Race competitor, was sympathetic: “We are offshore in the middle of nowhere, and on the chart, if you don’t go on the maximum zoom you can’t see anything.” He added, “When I was looking at the navigation a few days ago, checking these things, it took a long time for me to find [the shoals].” What the zoom giveth, the zoom taketh away.

In Praise of Paper Charts

When Vestas Wind hit the shoal in the Indian Ocean, Ron Wals, the president of OceanGrafix, producers of print-on-demand paper charts, did not miss the moment: “This incident is proof that although they’re convenient, using electronic charts alone is not enough to ensure a safe journey … There are just too many things that can go wrong, and we believe it’s wise to also refer to a paper chart.” Self-serving perhaps, but he has a point. With the roll of a track ball or the click of a mouse, vector charts give the navigator license to view the world at an inappropriate scale for a given situation in a way that a paper chart is incapable of.

Another misconception about electronic charts is that, because they run on computers, they are somehow more accurate than paper charts. They are not. The occupants of hydrographic offices around the world did not burst forth from their chambers to resurvey the globe the moment this technology came along. Whatever inaccuracies exist in our current chart catalogues are faithfully reproduced electronically. If the real-world configuration of a rock, ledge, or shoal is different from what the chart shows, no amount of gleaming gigabytes will change that.

By itself this is interesting, but here is why it matters: In days of old, like 10 years ago, when working on paper charts, you wouldn’t dare deliberately pass closer to danger than necessary because you operated with an abiding awareness of the uncertainties of your position, the limitations of your navigation skills, and the knowledge that even GPS coordinates and radar ranges take time to plot. Under the old system, you only knew where you’d been, never actually where you were at the moment, and this informed your choices. Without real-time information, you sensibly applied a healthy safety margin. Or in other words, your perception of risk shaped your behavior. But now, with our vessel displayed in real-time, eagerly swimming through a cerulean, electronic-touchscreen sea, we feel we always know exactly where we are, and this colors our perception of risk. Nowadays, we see people literally steering to port, then starboard, and back again, eyes on the chart plotter the entire time, shaving hazards closer than they ever would have in the past. And if a rock is not quite where the chart shows it, disaster ensues.

Trust your Eyes, Man

This is precisely what happened to the 113-foot, state-of-the-art motoryacht True North in Australia in 2004. The skipper grounded on a ledge while the chart plotter showed his vessel 700 feet away, in good water. It was a remote location and the surveys were old. On past trips he’d made the transit in daylight, using visual references and radar (a technology that avoids many of these issues entirely). But on this particular occasion, he arrived at night and relied upon the electronic chart to tell him what he needed to know. It didn’t.

Further evidence of erroneous positions being displayed on an electronic chart comes from personal experience. Not long ago, while securely tied to a dock in Norfolk, Virginia, our very good, USCG-approved electronic chart system depicted our vessel 150 feet away, hard aground, in a neighboring parking lot. We remained there for the entire three-day visit. But isn’t GPS accurate to within a few meters? It is, except, umm, when it isn’t. As homeport to the largest U.S. Naval fleet, charts of Norfolk are not likely to contain gross inaccuracies. Yet many mariners have noted similar position anomalies there and in other parts of the world. While I still can’t explain what we saw on the screen during that three-day hiatus, I knew I was not in the parking lot because my eyes told me so. And we did not encounter navigational difficulty either coming or going from port because we used our eyes and our radar, and they told a truer story.

By Way of Conclusion

It’s certainly true that electronic charts, both raster, and vector, are central to today’s approach to navigation. But they are not foolproof, especially vector charts. And the ‘come and go’ nature of displayed data has the power to facilitate human error in a way that a paper chart cannot. The sheer number of display choices that vector charts offer can be disorienting, leading to improper choices in certain situations. The impression that you have a complete picture of what is happening can also be misleading.

So the bottom line is pretty simple. Electronic charts cannot compensate for actual knowledge. On the contrary, the more I learn about E-Navigation, the clearer it is that you need to understand the basics so you can ask the important questions about what you are seeing, or not seeing. Sometimes, advanced equipment can lead not to an error-free world, but rather to new ways of making mistakes.

This article originally appeared in the April 2015 issue of Power & Motoryacht magazine. Updated September 19, 2017.